Gabrielle Hogg is an autisticadvocate and AAC user based in New Zealand. She blogs over at [AutismoGirl], post Facebook, and also is on twitter.

A few years ago we co-developed a one page handout to help psychologists, counsellors, and other clinicians support autistic people and those who use AAC part or full time.

There are many standard practices that work well for neurotypical people that can be challenging for autistic people, people with language disorders, or those with other communication impairments.

For example, many people I support find open ended questions incredibly stressful because they don't know what is expected of them, how much or little detail is being asked for, or where/how to start.

Therapists typically put a lot of thought and effort into making a room comfortable and safe, but the details of how they do so may not have the same effects on autistic people. It can be hard as a client to know if it is okay to ask for the curtains to be drawn to reduce glare,florescent lights to be turned off, or for the therapist to sit at a different angle.

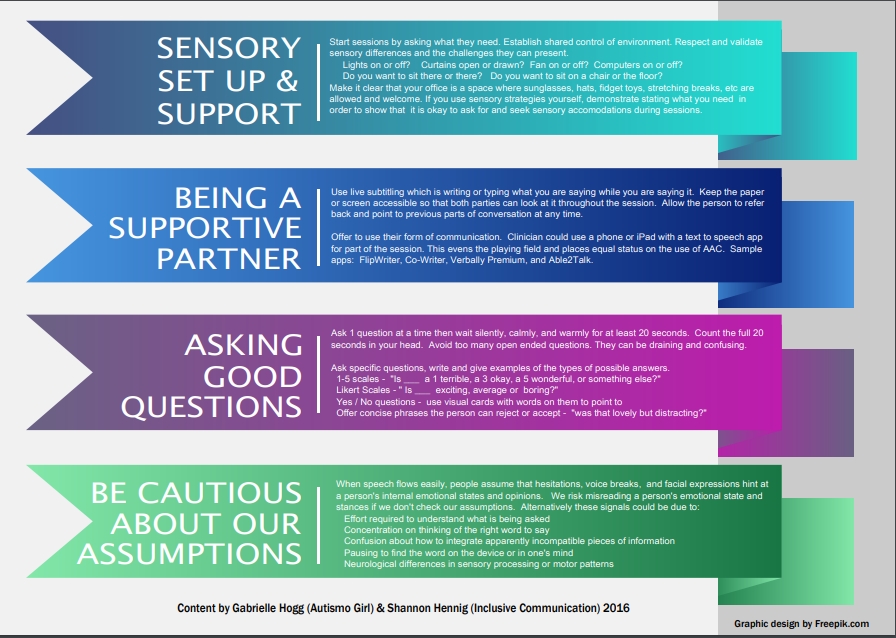

Here is a PDF of the handout we jointly developed that break down our suggestions into 4 sections:

-

Sensory support and set up

Being a supportive communication partner

Asking good questions

Be cautious about our assumptions

Note - We carefully and thoughtfully choose to use the phrase "autistic individuals" as this is a way to respect our belief that being autistic is part of the natural Neurodiversity of individuals. We respect and embrace this diversity. That said, we fully respectthat some individuals and families prefer person first language such as "person with autism".

UPDATE 28 February 2018

A collegue (who is both autistic and working in mental health) recently shared a link to some some great information in the New Zealand Autism Spectrum Disorder Guideline supplementary paper on cognitive behaviour therapy for adults with ASD (page 62)

- Use a structured approach and minimise anxiety about the therapeutic process by being explicit about roles, times, goals and techniques.

- Extend the number of sessions and time provided to conduct tasks to accommodate slower information-processing and the mental demands of the therapeutic process. Be flexible about the length of each session and offer breaks to allow for cognitive and motivational deficits.

- Provide psycho-education about autism, emotions, and mental health challenges relevant to the client.

- Concentrate on well-defined and specific difficulties as the starting point for intervention, with less emphasis on changing client’s cognitions.

- Be more active and directive in therapy, where appropriate, including giving suggestions, information, and immediate and specific feedback on performance. Examine the rationale and evidence for inaccurate, automatic thoughts and collaboratively develop alternative interpretations, concrete strategies and courses of action.

- Teach explicit rules and their appropriate context, including the use of verbal, nonverbal and paralinguistic cues to a social situation.

- Incorporate specific behavioural techniques where appropriate, such as relaxation strategies, meditation, mindfulness, thought stopping or systematic desensitisation.

- Communicate visually (e.g., using worksheets, images, diagrams, 'tool boxes', comic strip conversations, video-taped vignettes, peer modelling, and working together on a computer).

- Avoid ambiguity through minimising the use of colloquialisms, abstract concepts and metaphor. Use specific and concrete analogies relatable to the client’s concerns.

- Incorporate participants' interests in terms of content and modes of content delivery to enhance engagement.

- Involve a support person, such as a family member, partner, carer or key worker (if the person with autism agrees) as a co-therapist to improve generalisation of skills learned within sessions.